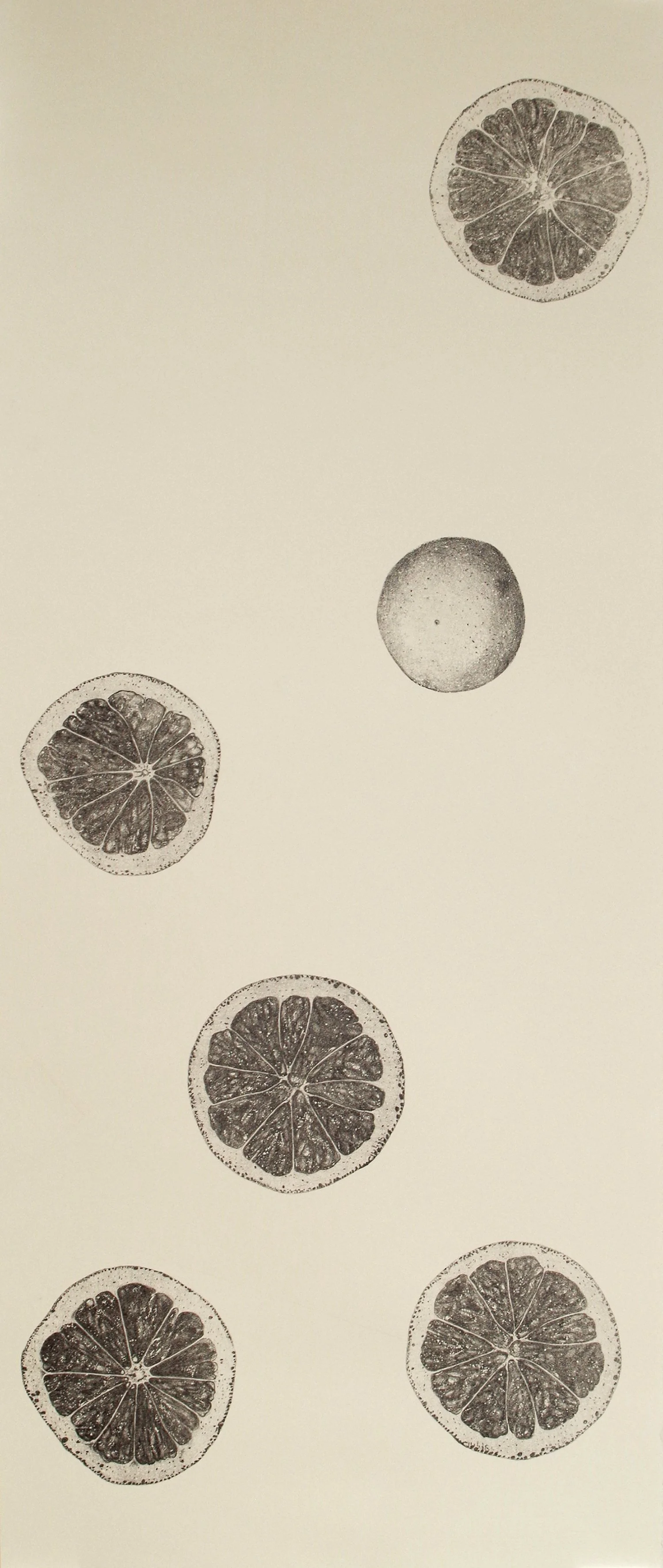

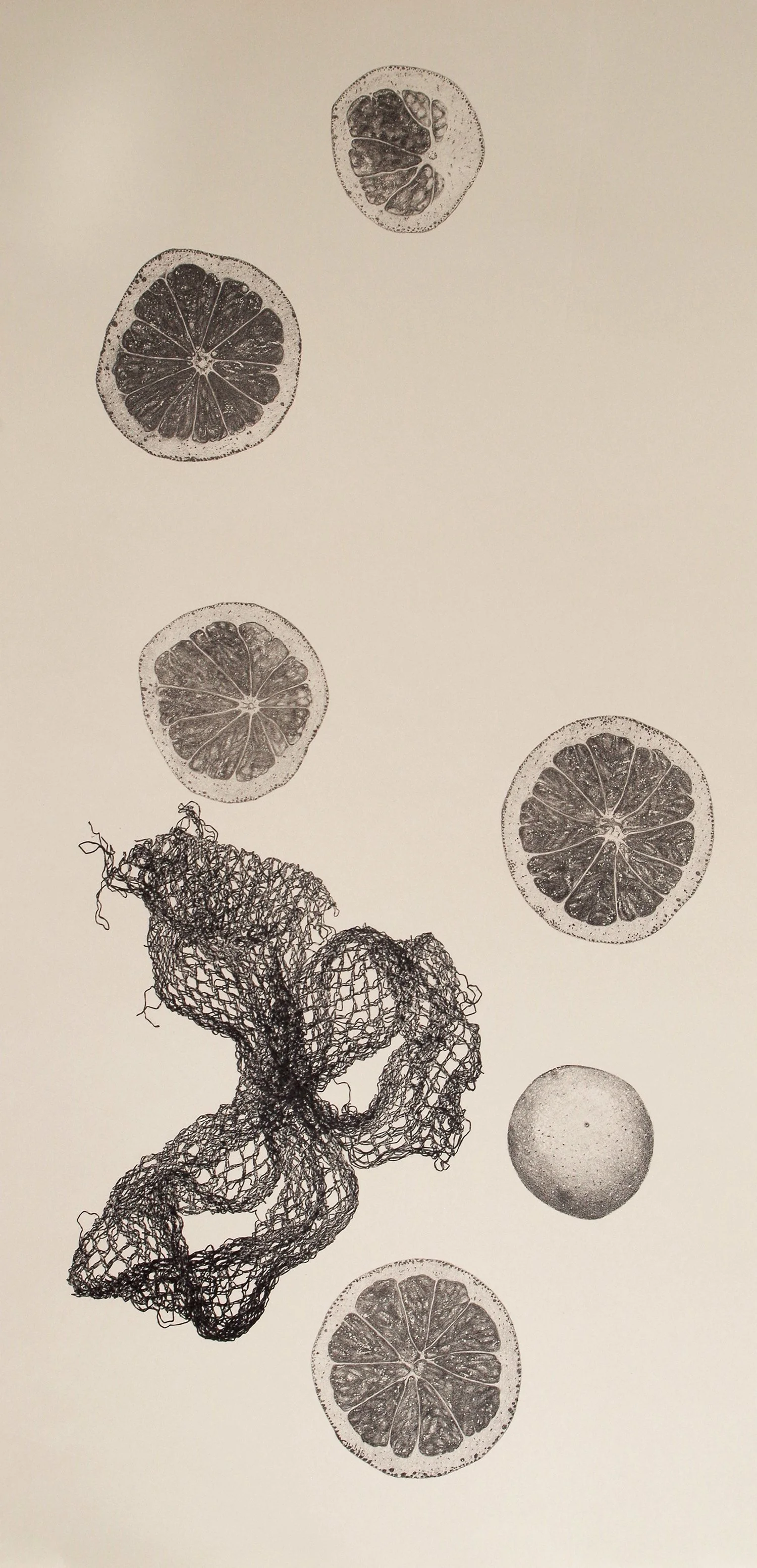

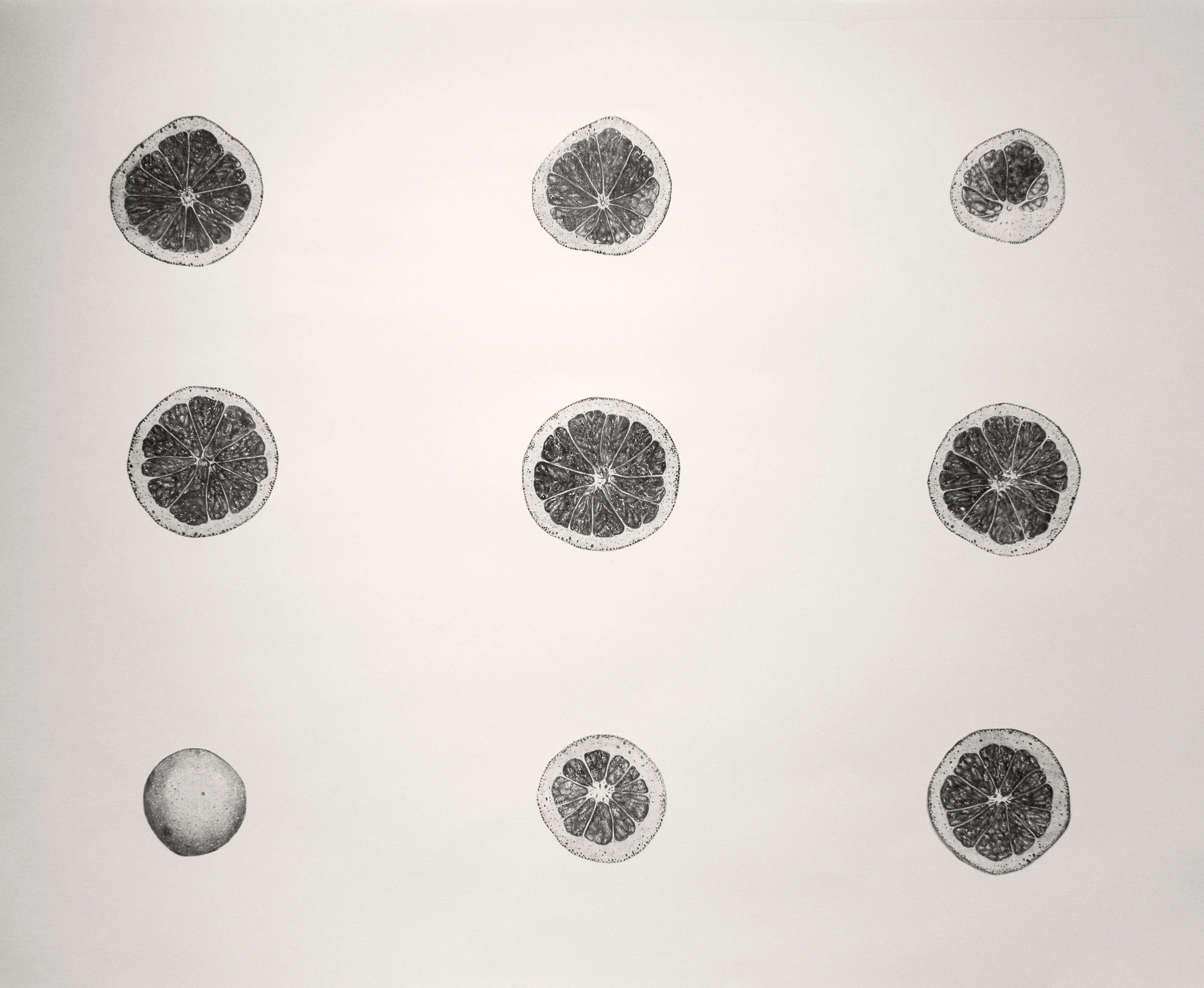

Lithography (from Ancient Greek λίθος, lithos ‘stone’, and γράφειν, graphein ‘to write’) is the art of printing from stone. The stones used in this process are slabs of Jurassic limestone from the Solnhofen region of Bavaria, geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation. The stone was formed as coral reefs grew up in the Tethys Sea and restricted the flow of water inland, creating isolated lagoons where salinity rose to levels that were too high for most living things. Creatures who made their way into the lagoons in one way or another were left undisturbed by scavengers when they died. In their calm and anoxic resting places they petrified along with the silt sands of the lagoon into fossils delicate enough to record insect wings, feathers, or the soft bodies of jellyfish.

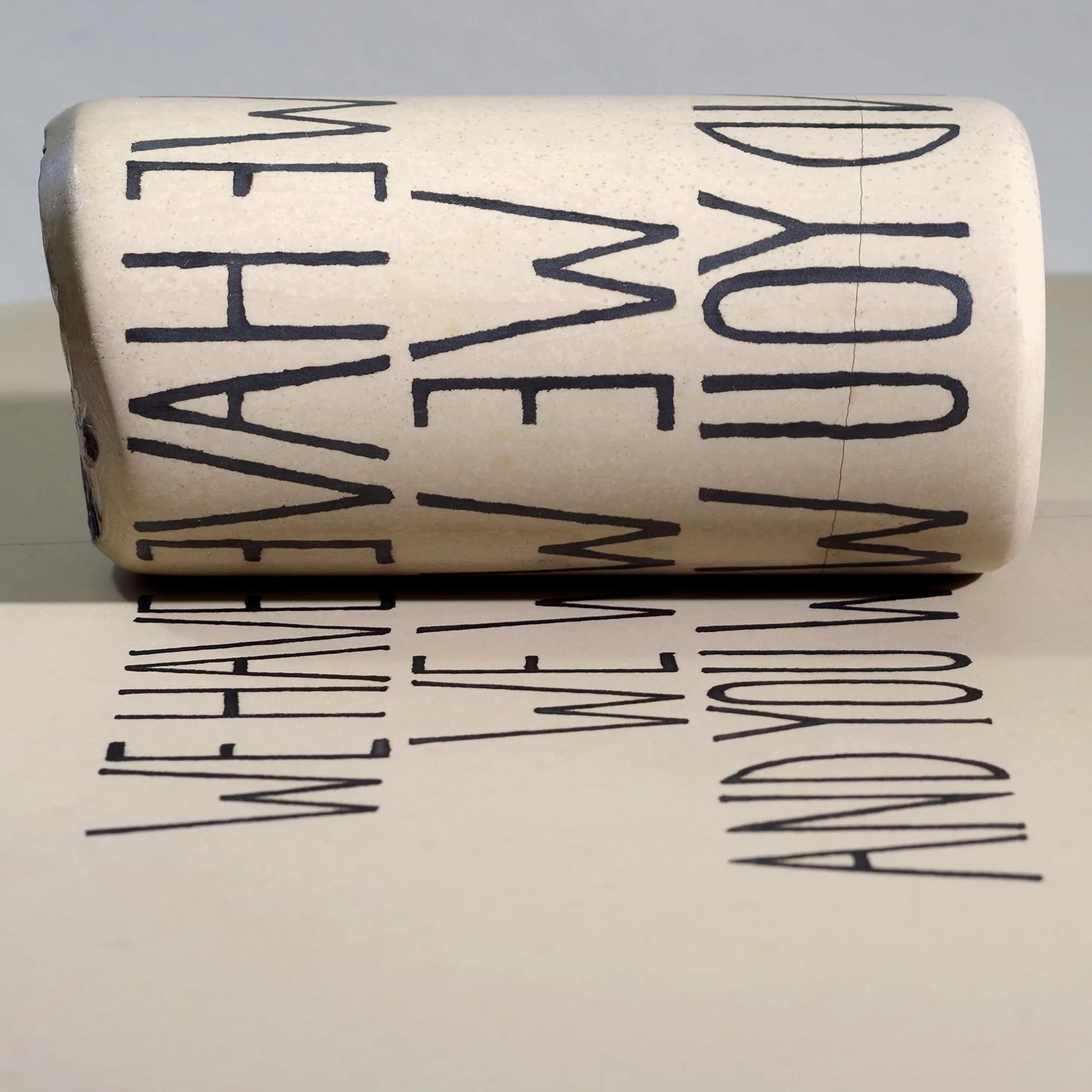

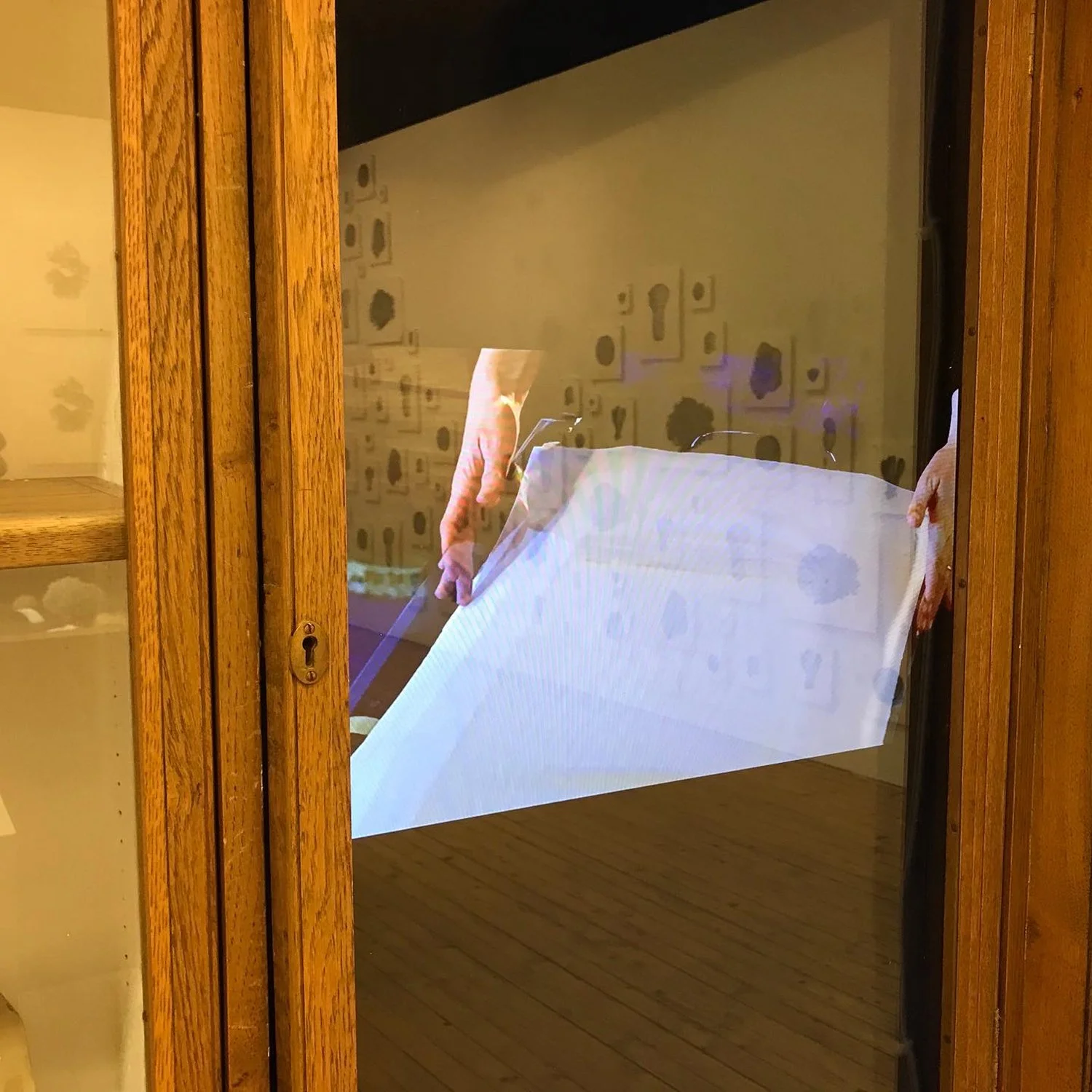

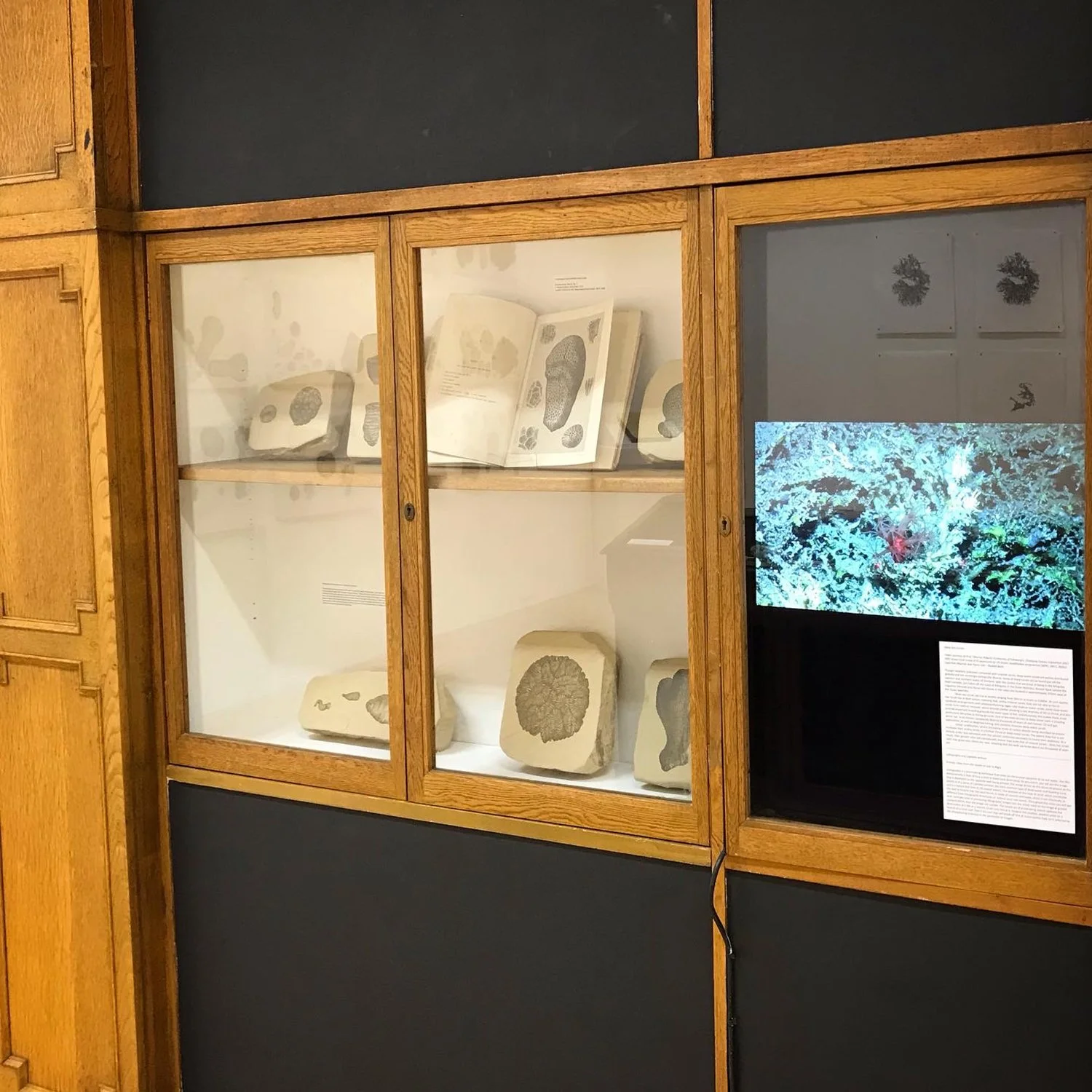

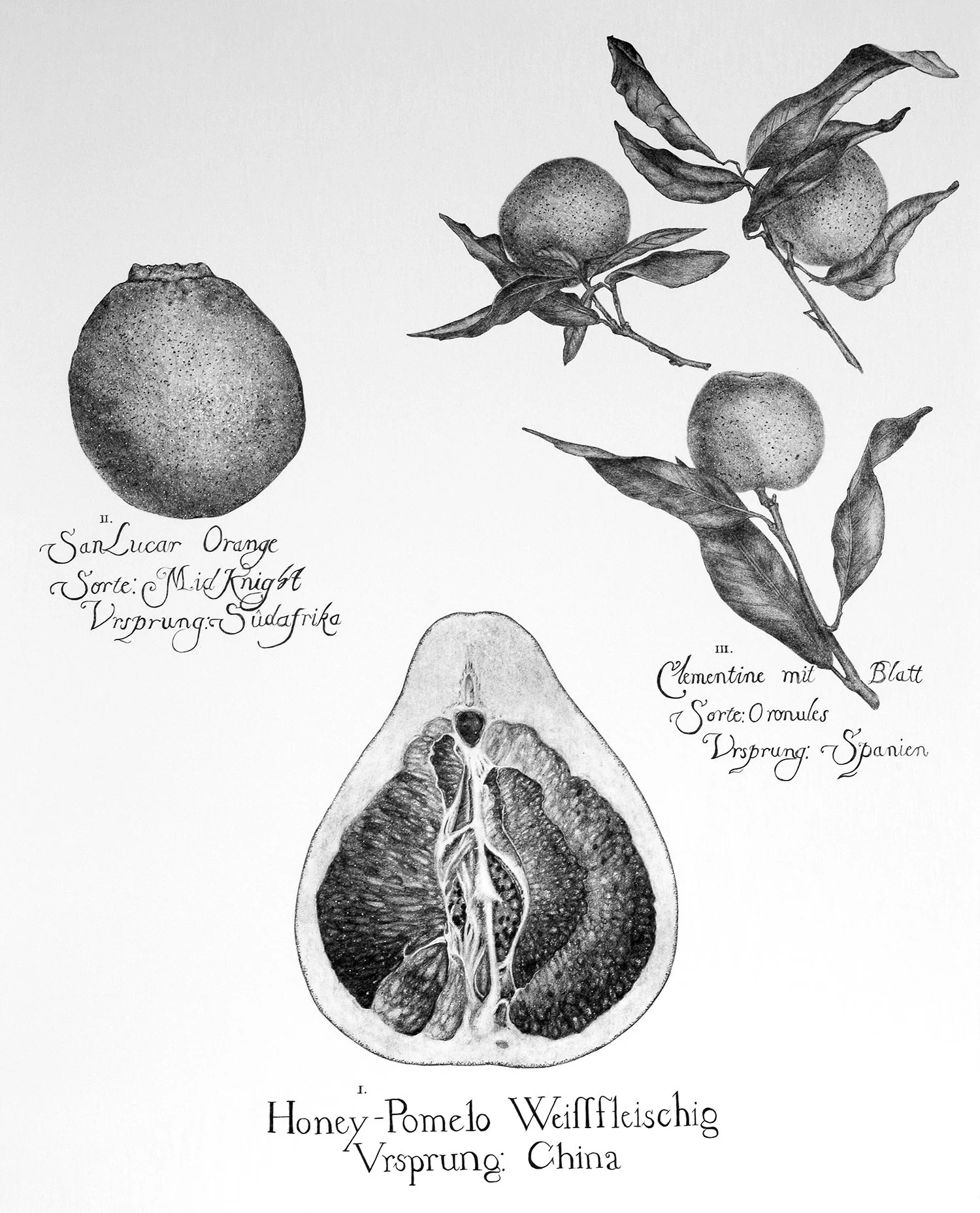

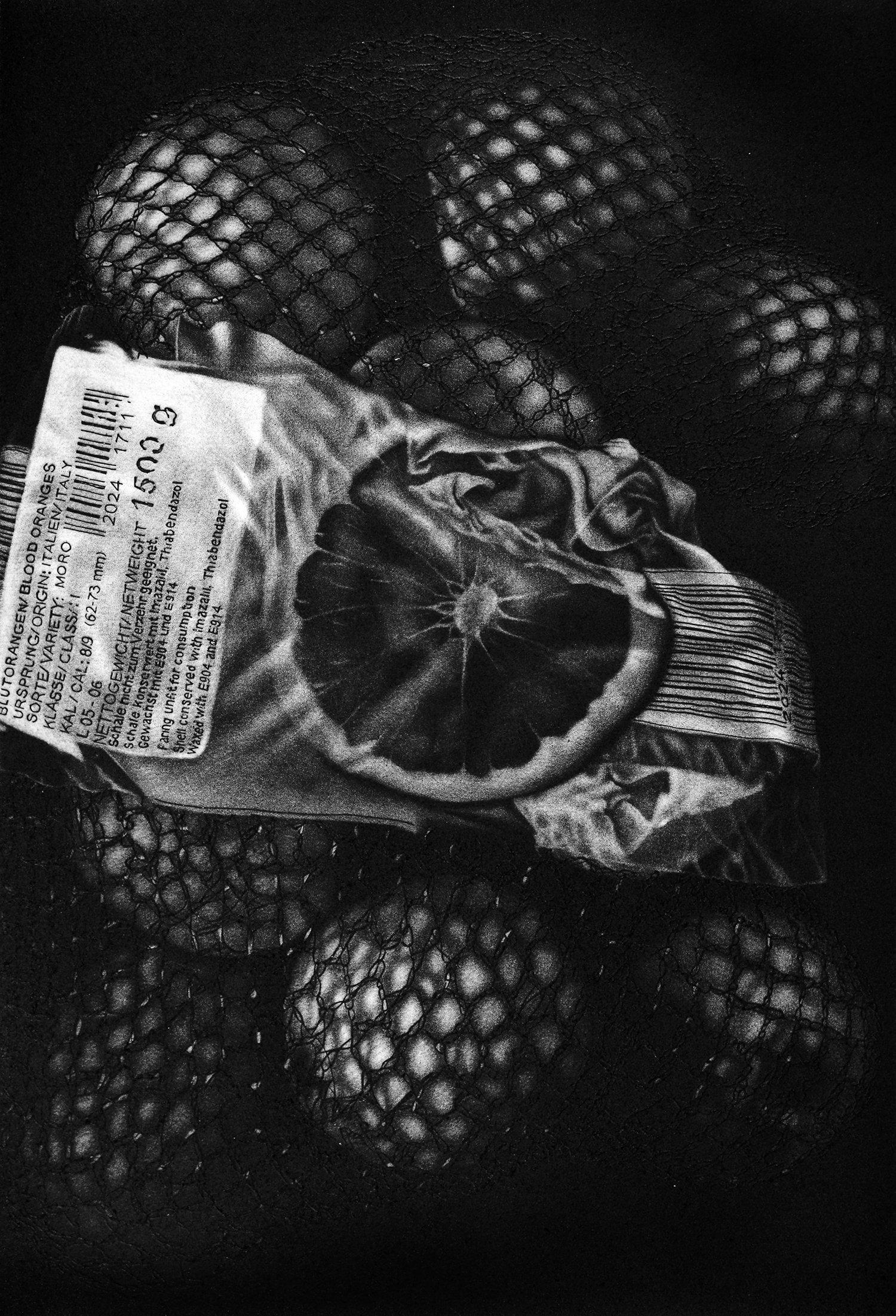

In the late 1700s, the cost of copper used to make printing matrices encouraged innovation and a search for alternate materials for producing prints. The dense and pure limestone which was then abundant in the Altmühl Valley was discovered to be the perfect vessel for a process of chemical printing based on the tendency of oil and water to repel each other. Images were drawn onto the surface of the stones with fatty materials, then the water-based resin gum arabic was mixed with saltpetre (nitric acid), which caused the traces of the fatty drawing materials to be absorbed into the stone so that, when wetted, the stone would be receptive to oil-based inks for printing.

During the century following this discovery, limestone was extensively quarried in the region. Global demand for printing stones encouraged exploration of limestone deposits further afield, but Solnhofen limestone’s density and the characteristic large slabs of thick and consistent stone meant that Bavaria was the main source of lithographic limestone. By the early 1900s, deposits of limestone judged to be of a high enough quality to be considered ‘lithographic standard’ were almost entirely exhausted, though the shift to using metal plates for commercial printmaking, as is still the case today, meant this was not a disaster for the printing industry.

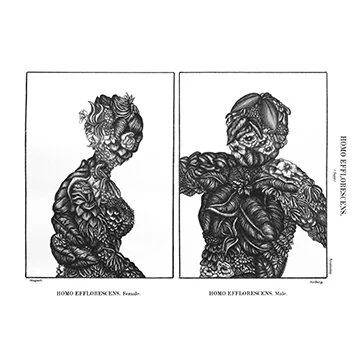

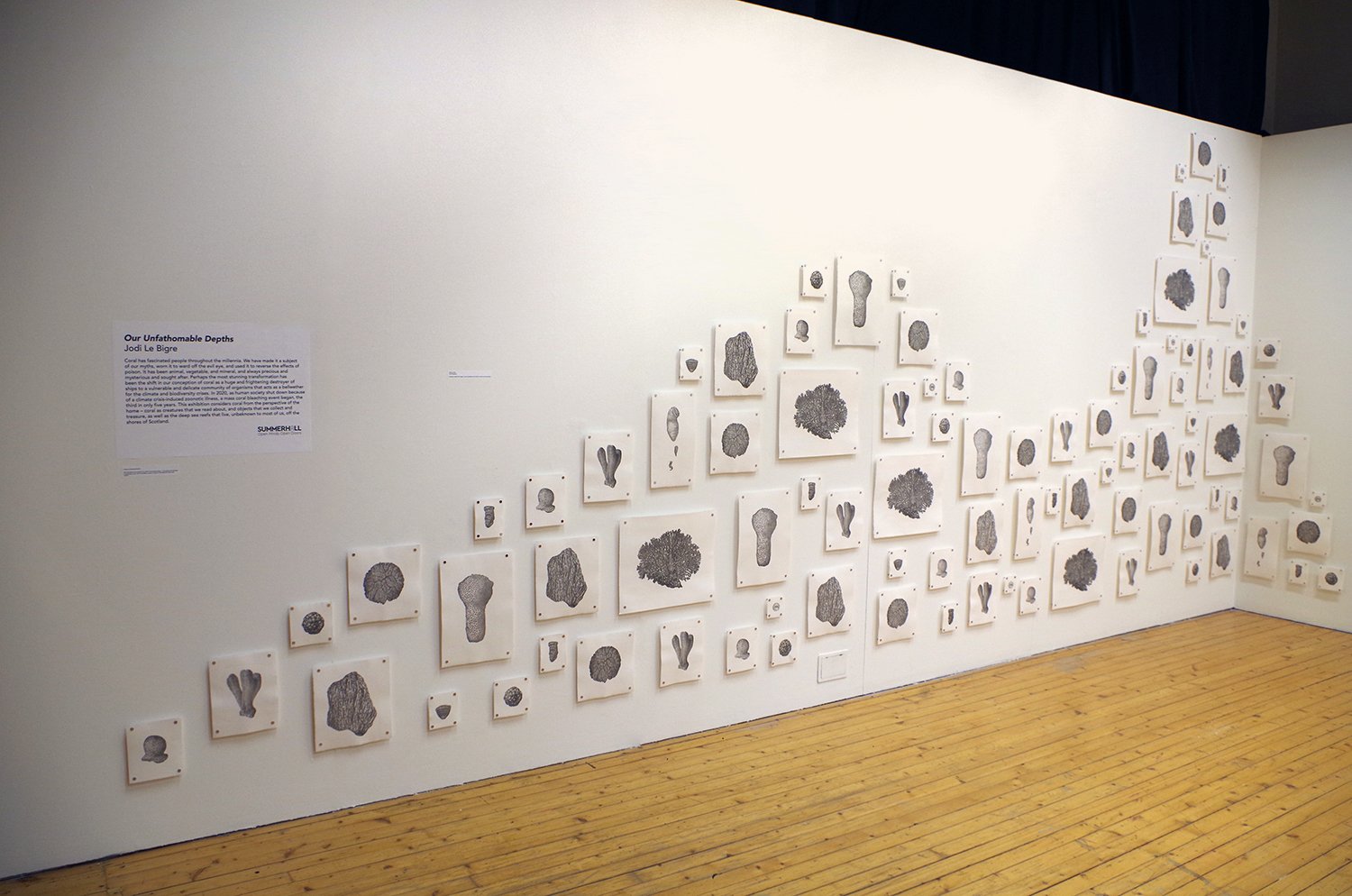

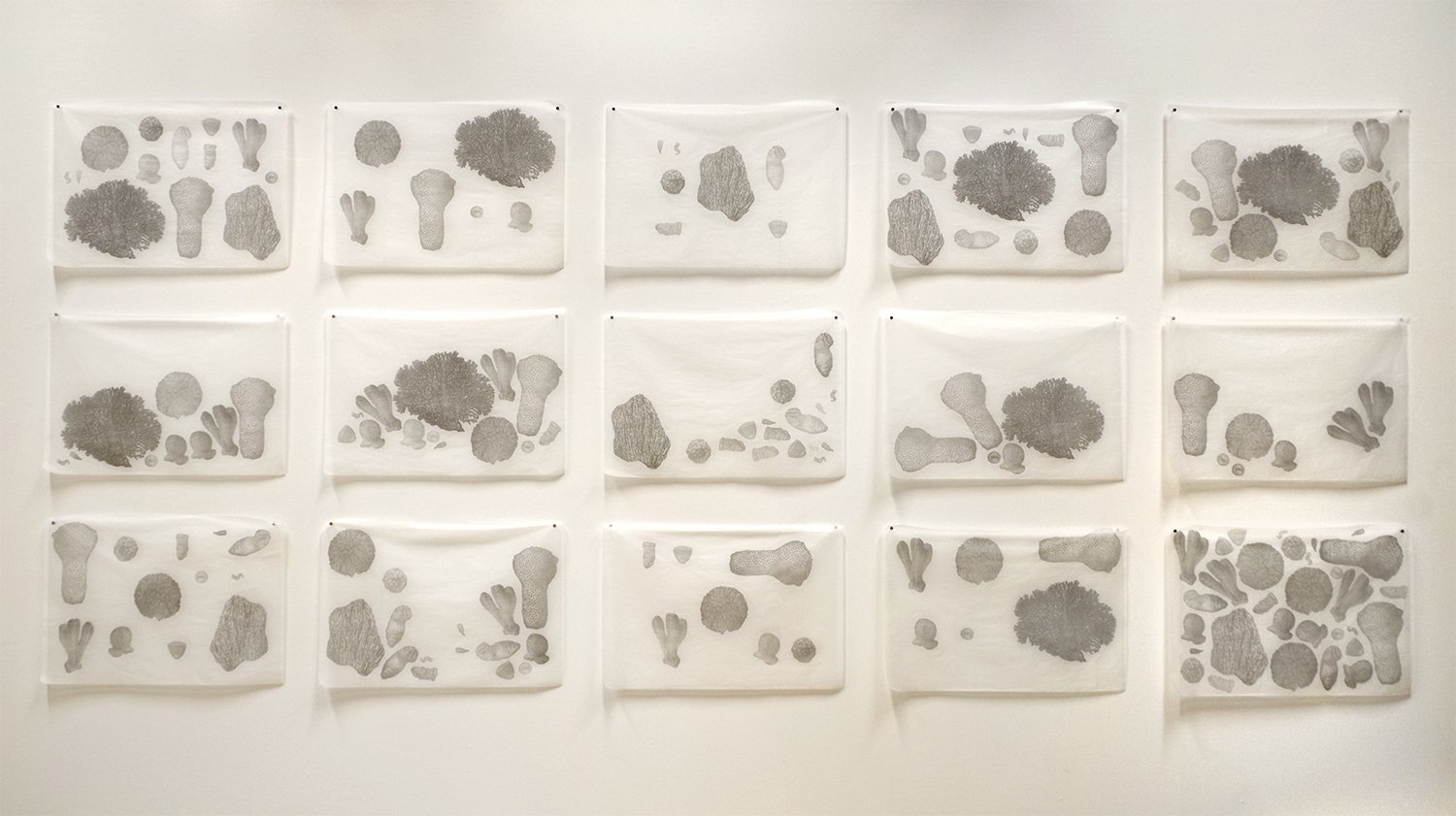

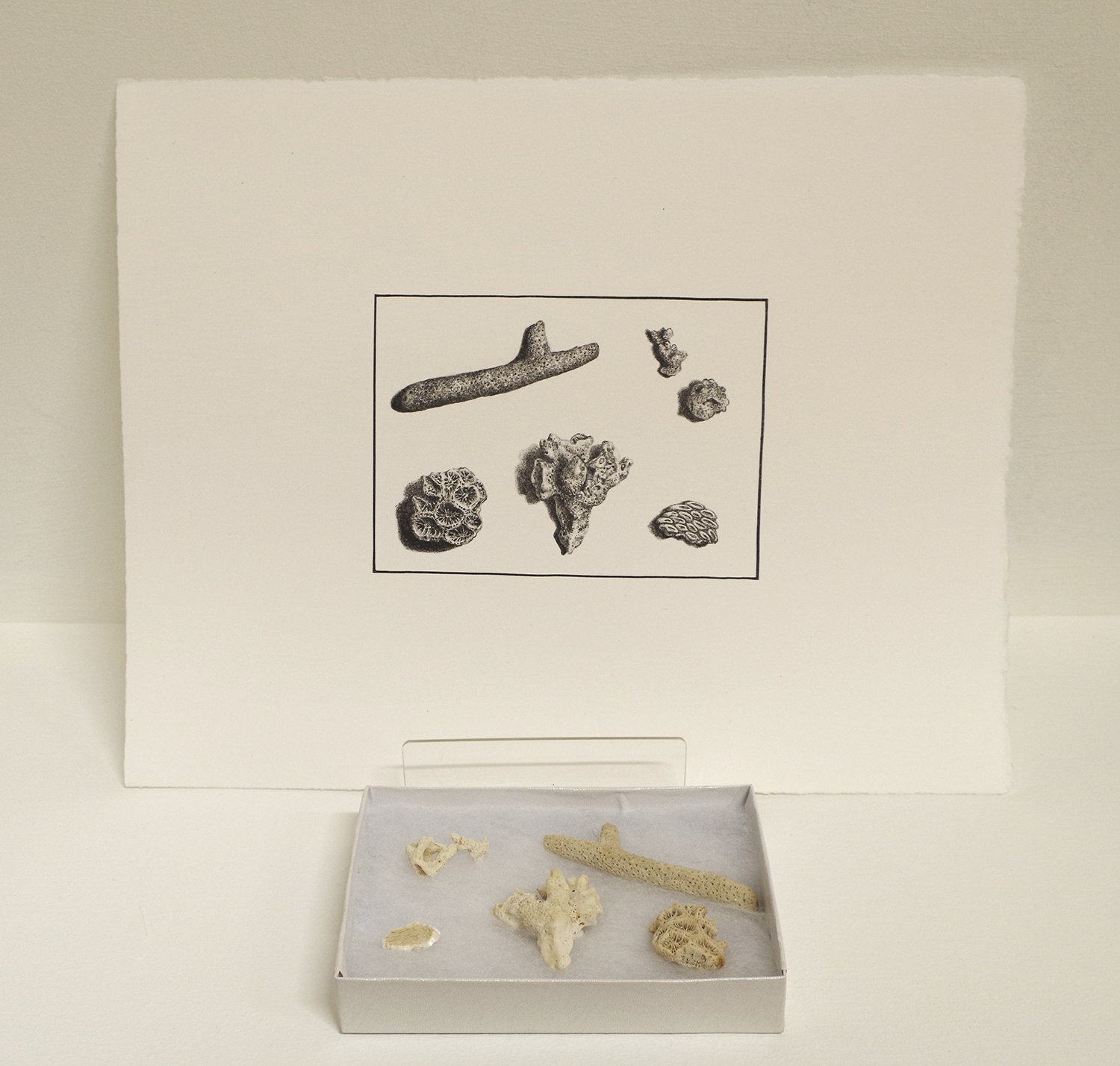

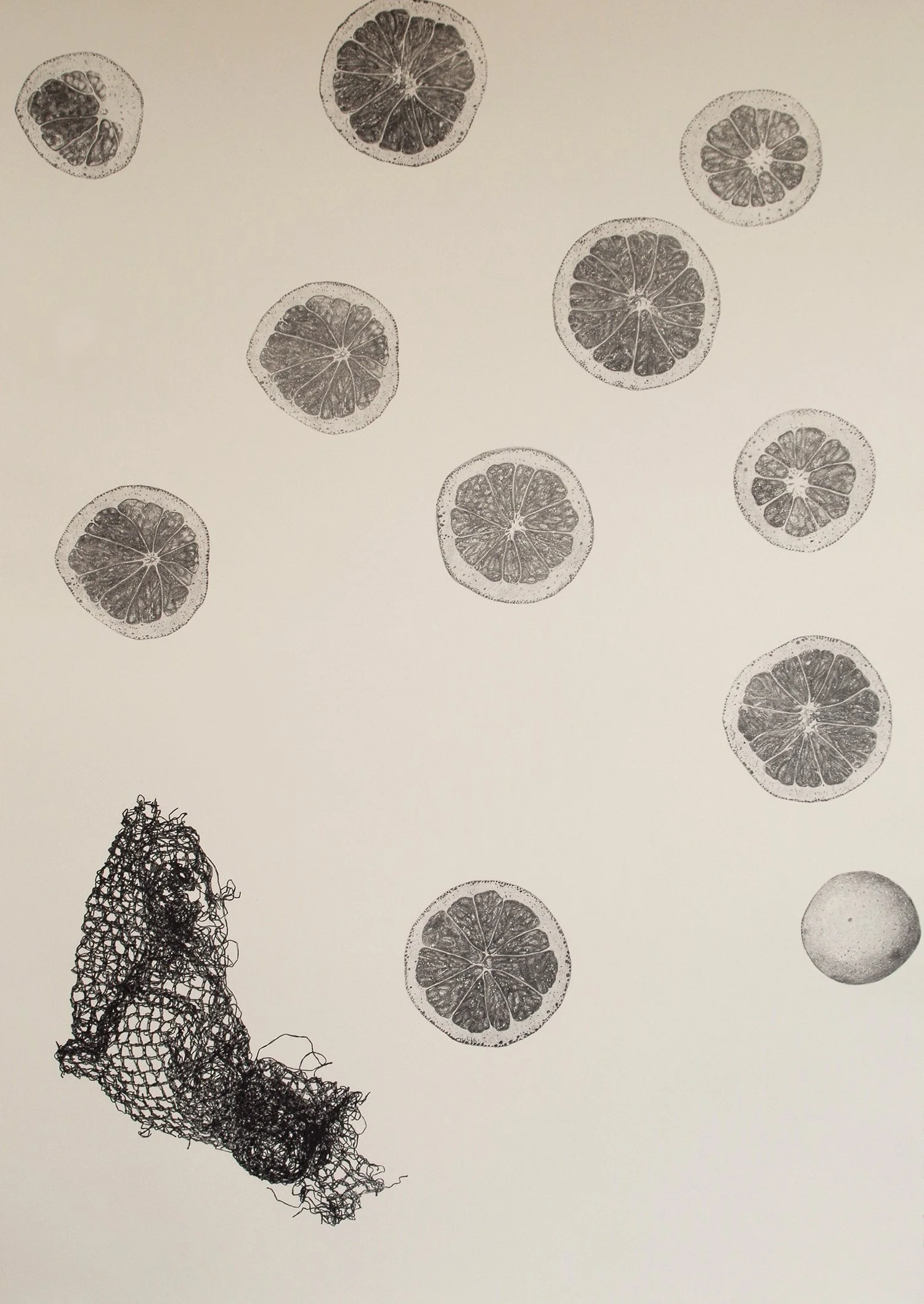

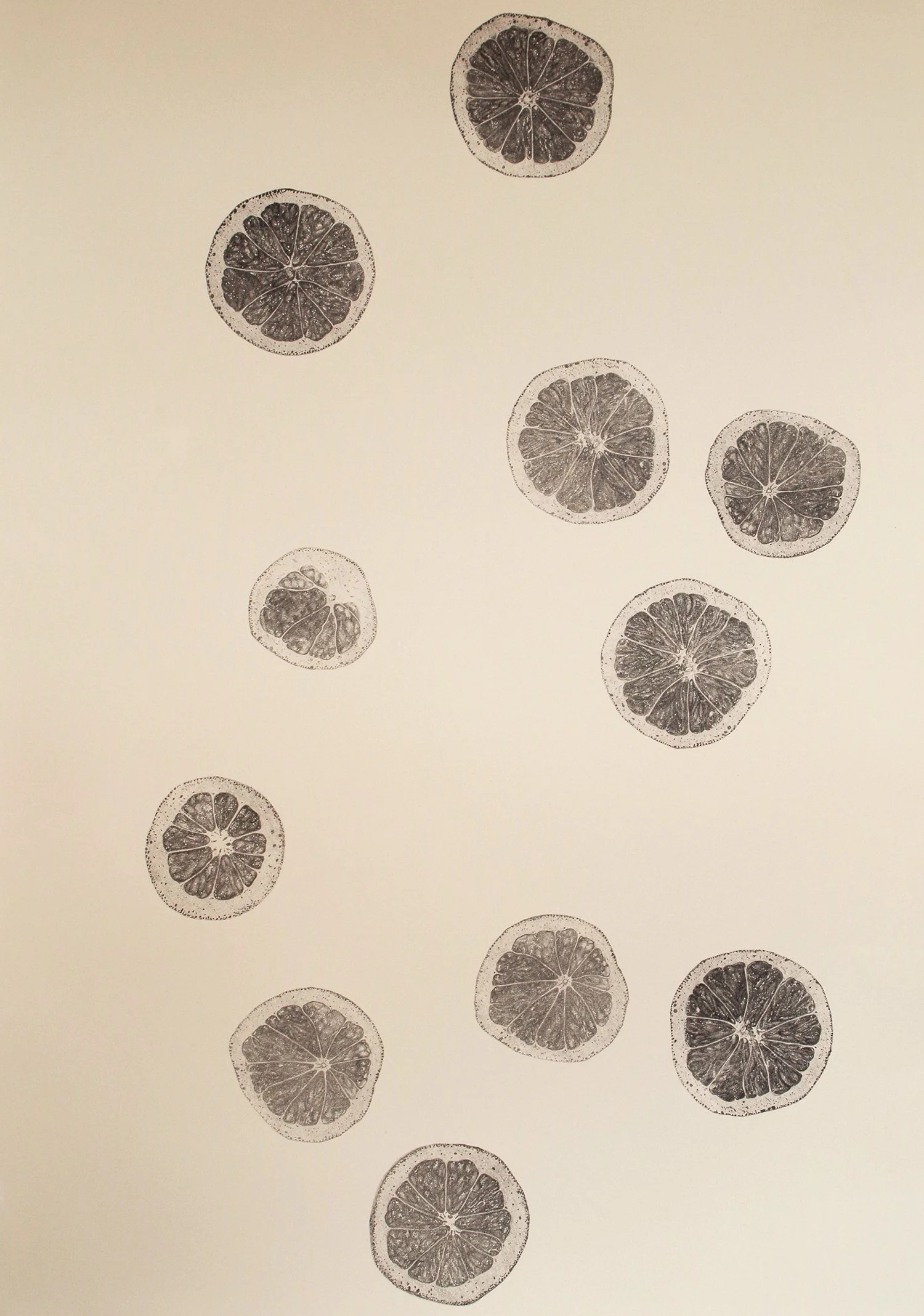

Lithography on stone exists today as the legacy of this brief period in the history of publishing and extraction. The stones that artists use currently are the remnants of publishing innovation and environmental plunder. Millions of years old, these stones have, in more recent years, weathered time in artists’ studios, publishing-house basements, as well as being repurposed as paving or building stones. Images can be placed into the stone and removed from them. As the stone is worn down through use, sometimes fossils are found. Working on the stone can feel like a meditation on deep time, depletion, and creation. The stones themselves can be understood as a co-creation of the corals who formed the lagoons, the calcium carbonate of the limestone referencing the skeletons of these coral collaborators in the lithographic process.